Downtown Chadron, Neb. USDA/Flickr (Public Domain).

In national polls, confidence in various government institutions had declined last year after increasing slightly in 2020. However, people are more likely to have confidence in local institutions compared to national ones. In fact, Gallup has found that confidence in local government remains higher than state government, which is higher than the federal government. Given this, how much confidence do rural Nebraskans have in various government institutions and systems? What factors influence their confidence?

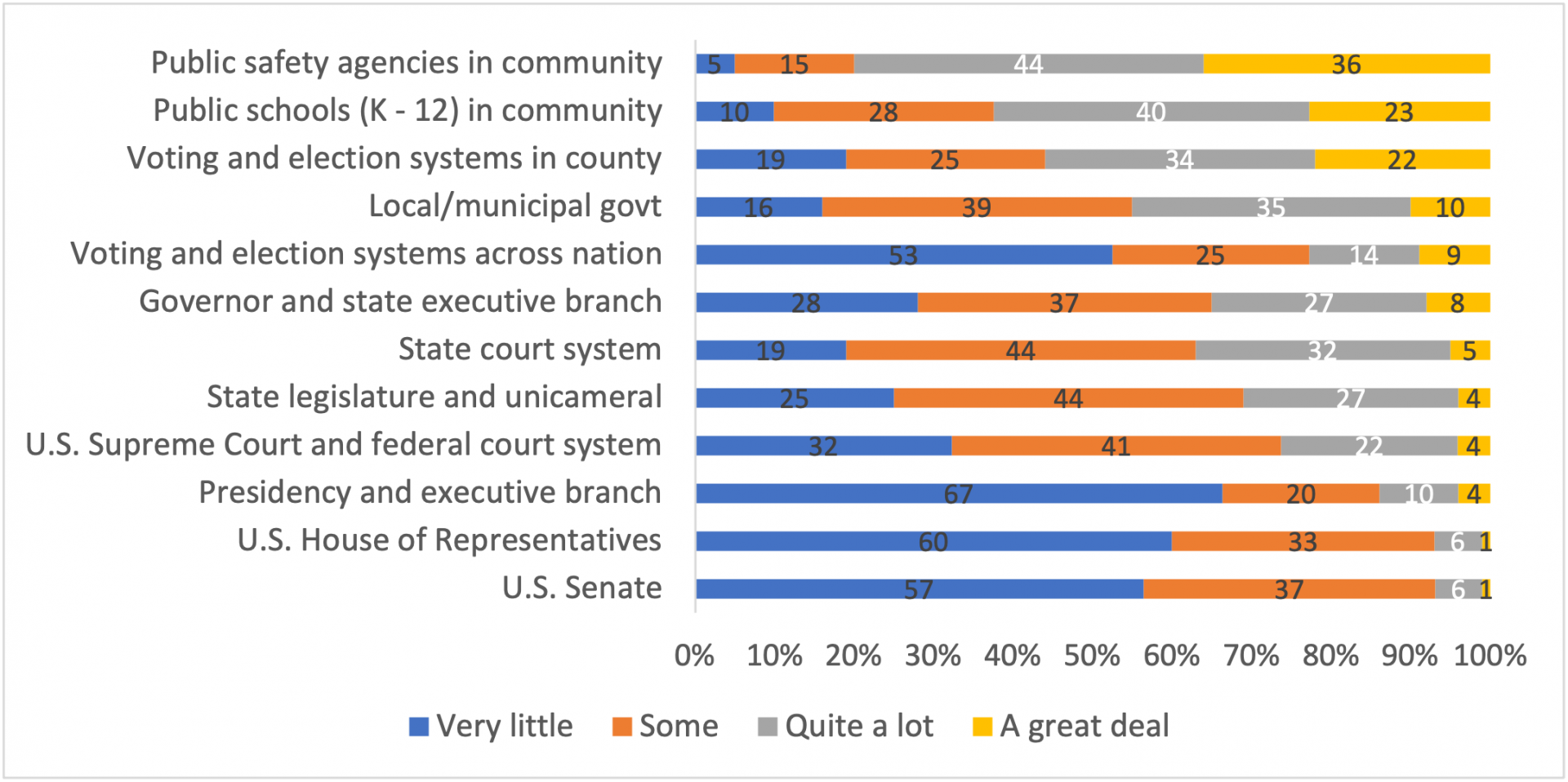

The 2021 Poll looked at how confident rural Nebraskans are with various institutions. Respondents were asked to indicate how much confidence they have in a list of 12 institutions. Overall, most rural Nebraskans have confidence in their local institutions (public safety agencies in their community, public schools in their community, and voting and election systems in their county). However, most have very little confidence in many national institutions (the Presidency, the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, and voting and election systems across the nation). Over one-half of rural Nebraskans have quite a lot or a great deal of confidence in public safety agencies in their community (80%), public schools (K – 12) in their community (63%) and voting and election systems in their county (56%). On the other hand, most rural Nebraskans have very little confidence in the following national institutions: the Presidency and executive branch of government (67%), U.S. House of Representatives (60%), U.S. Senate (57%) and voting and election systems across the nation (53%). Thus, rural Nebraskans follow the trend of trusting local governments more than national ones.

This trend can be explained by the proximity of local government, its accessibility, and the easily observed policy outcomes (Wolak and Palus, 2010). Local governments are closer to the people with perhaps more interactions and thus can be seen as being more responsive and representative. This can especially hold true in smaller communities where residents are more likely to personally know their government officials. They may attend the same church, have children in the same school activities or see them often in local businesses. It is also easier to attend a local town hall or a school board meeting than to attend a hearing at the state legislature or at the national level.

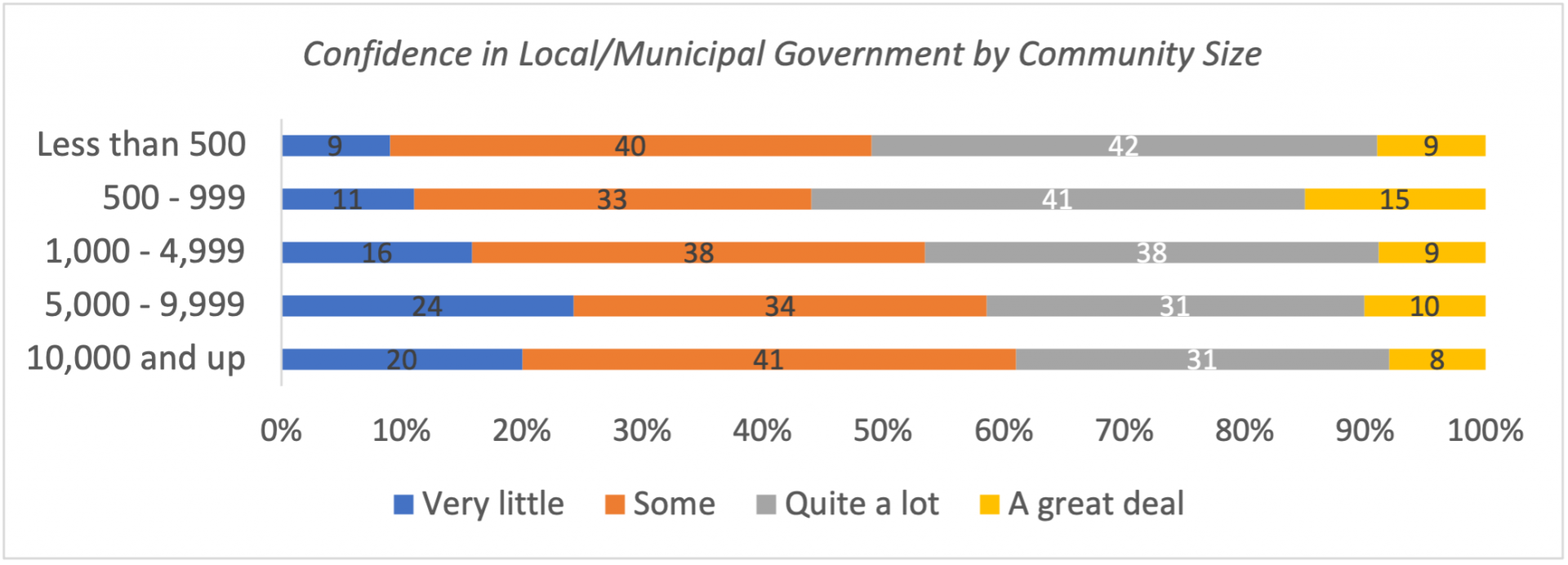

This hypothesis is confirmed when looking at the relationship between community size and confidence in their local government. Persons living in or near smaller communities are more likely than persons living in or near larger communities to have confidence in their local/municipal government. At least one-half of persons living in or near communities with populations less than 1,000 have quite a lot or a great deal of confidence in their local/municipal government, compared to less than four in ten persons living in or near communities with populations of 10,000 or more.

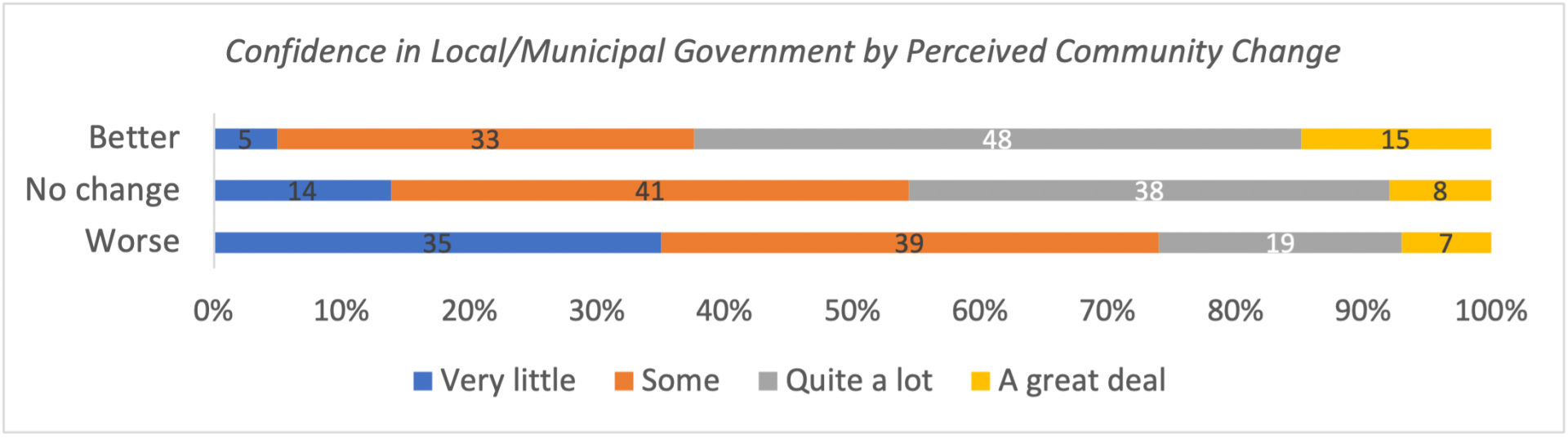

Are other factors related to confidence in local institutions? Trust in government studies have shown that evaluations of performance are important in explaining confidence in the national government (Wolak and Palus, 2010). Does this hold true for local government? If people are more positive about their community, are they more likely to have confidence in their local government? The Rural Poll asked respondents to assess the change in their community during the past year as well as their expectations of the direction of their community in the future. Specifically, they were asked, “Communities across the nation are undergoing change. When you think about this past year, would you say...My community has changed for the...” Answer categories were better, no change or worse. And, “Based on what you see of the situation today, do you think that, ten years from now, your community will be a worse place to live, a better place or about the same?”

There is a relationship between perceived community change and confidence in their local government. Persons who think their community has changed for the better during the past year are more likely than persons who feel their community changed for the worse to have a great deal of confidence in their local government. Fifteen percent of persons who said their community changed for the better during the past year have a great deal of confidence in their local government, compared to approximately 8% of persons who believe their community changed for the worse or experienced no change.

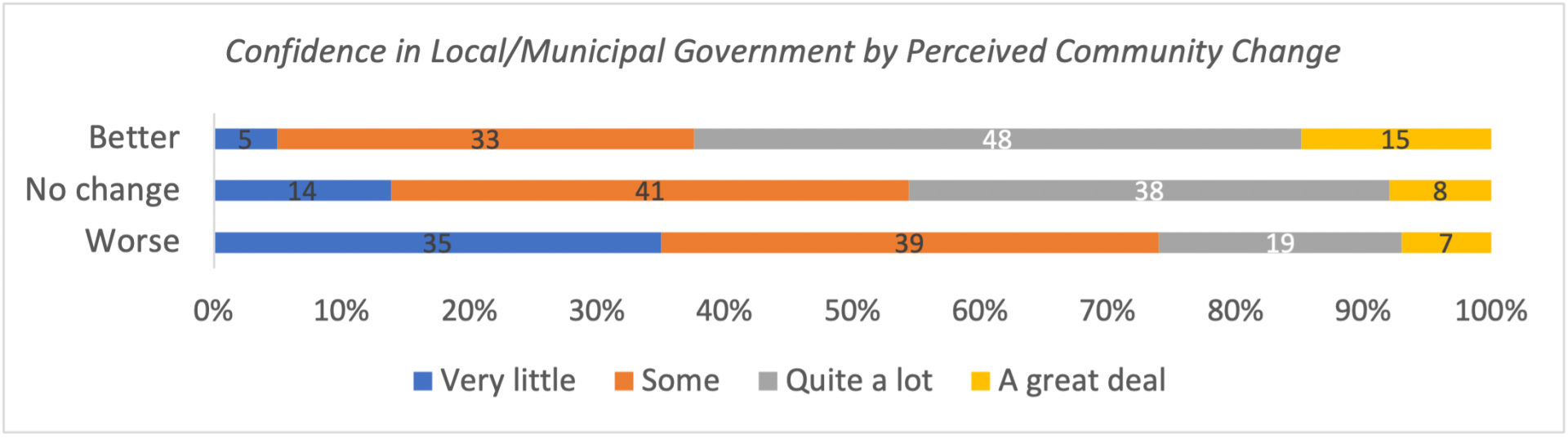

Similarly, persons who believe their community will be a better place to live 10 years from now are more likely than persons who believe it will be a worse place to live to have confidence in their local government. Fourteen percent of persons who believe their community will be a better place to live 10 years from now have a great deal of confidence in their local government, compared to 8% of persons who believe their community will either be about the same or a worse place to live.

Trust in local institutions is important to understand. Strong local governments are key to thriving communities. Thus, it is encouraging that rural Nebraskans are overall satisfied with their local institutions. And, while smaller communities may have less resources and a smaller pool of local candidates for government positions, it is also encouraging that residents of these smaller communities have higher levels of confidence in their local government. The relationship between perceived community change and expected future change with confidence in local government can support the hypothesis that past performance can influence confidence.

Reference: Wolak, J., & Palus, C. K. (2010). The Dynamics of Public Confidence in U.S. State and Local Government. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 10(4), 421–445. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41427034